Headnote: Should I curate a legacy twin? Last week I wrote about the effect these digital representations can have on bereaved families and friends. Time now to get more personal and turn to the other half of the question: Should I create my own legacy avatar to outlive me?

I'm in my 80s, and chances are good I won't be around too much longer. Last month I started this Substack, Mind Revolution, partly to create a legacy, to share my views on the unprecedented upheavals transforming our world. After decades of researching and writing books exploring ways humans generate meanings in an otherwise meaningless world, I realized that AI works as a radically new type of meaning maker.

I wanted to share what my studies suggest about how these intelligent machines are transforming our inner lives. These posts will be my intellectual legacy, fitting since I have spent so much of my life "in my head."

But my two recent posts about digital twins have gotten me thinking about a different kind of legacy, something less abstract and more intimate. These new technologies make it possible to preserve parts of ourselves in strikingly lifelike ways.

I could curate a digital twin to go on "living" after I’m gone. Hundreds of thousands of people have already embraced this new kind of legacy.

Should I give my surviving family and friends a Houston Wood avatar? How would this choice affect them and my remaining years?

Legacy Twins

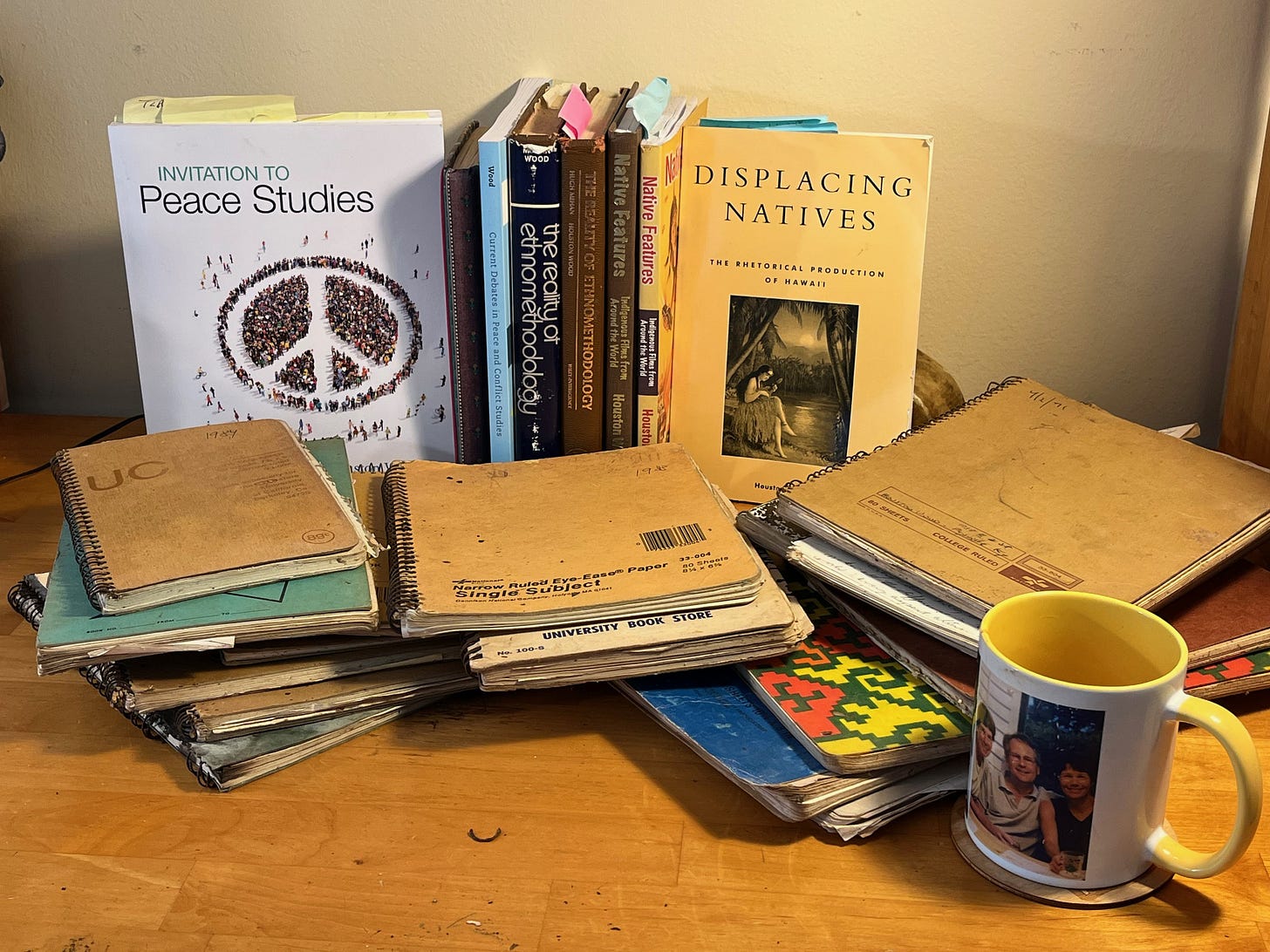

Right now, for $10,000, near the price of an average American funeral, I could build a fairly comprehensive database to guide my AI twin's conversations and behavior. I could digitize my twenty-four handwritten journals (the first begun when I was nineteen), along with my published books and unpublished manuscripts, and also add the few dozen letters I've saved from decades ago. I could upload hundreds of pictures and a few dozen videos of me, my family, and friends, as well as emails, document files, social media, and metadata from my computer and the cloud. I would want to execute a FOIA request to include my FBI dossier from the years the government tracked me as a "person of interest," a potentially dangerous subversive of Nixon’s America.

I would definitely also want to spend a few hours making videos where I answered questions about my life like those that StoryFile has developed to guide people in recording their memories and opinions, a kind of systematic biographical interview I've never given anyone. (The uncanny digital twin of William Shatner that StoryFile showcases on its website first drew my attention to the potential of legacy twins.)

This data would be the basis for a high-definition video avatar that looked, moved, spoke, and gestured enough like me to carry on conversations as a convincing Houston Wood for decades after I'm gone.

In a few more years, as the technology advances, this same data could be repurposed to create a 3-D hologram, as well as generate virtual and mixed reality Houston avatars that can talk with friends and family, and other legacy avatars. By mid-century, my data might be repurposed to construct a Houston robot, a full-body replica that speaks and acts just like me, except it'll be a machine.

The robot is someone else's future. But the avatar? That's my decision to make right now.

Why I'm Tempted

I can think of several reasons why I should create a twin.

I have participated in several Buddhist-inspired memento mori workshops preparing people to die with equanimity. Curating a legacy digital twin would force me to repeatedly acknowledge my own mortality. "I am of the nature to die," I was taught to recite in those workshops. "Nothing I do can keep me from dying."

This remembering work isn't morbid. It's comforting, a practice of increasing acceptance of what is inevitable. Building a digital legacy as a memento mori practice sounds promising to me.

The grief tech companies say that creating a digital twin can help people find more purpose in their lives. The curation process shifts focus from dying onto the practical task of constructing an artifact that will last much longer than traditional legacies like memories and photos. Creating my digital twin could feel like a way of continuing part of my life. As I did the work, maybe death would seem for a while as much about making decisions as about facing a permanent end.

There is also the likely benefit of curation forcing me to reflect on my life. I have a strong tendency to be forward-looking, as my posts here on Mind Revolution make clear. But it might be good to pause and think systematically about what I have done and who I have known and loved. Making choices about what to include in the database could force self-reflection about my past, a practice I tend to avoid. Maybe I would glean some wisdom, even some pleasure, from remembering the person I once was. These new insights could be added to my data so my legacy twin could draw on them in its future conversations.

I likely wouldn't die right after I finished my twin. So, there I would be, living maybe even for years with a Houston avatar I could talk to anytime I wished. That would be very strange at first, but maybe soon seem simply more like reading and writing in my journal than entering the uncanny valley. My avatar would probably enjoy my sense of humor more than the people I know do. And I wouldn't have to worry about offending it, or appearing stupid, worries I often have when I talk. We could mock and make fun of each other like only best friends and siblings can.

I could feed these dialogues back into the database, too, further enriching the legacy twin I would be leaving for others. Or, I can imagine, if my conversations with my avatar went on for too many years, I might feel the avatar has already served its purpose and ask it to be declared dead when I am.

But that's probably not what I or most people who use grief tech will do. The goal is to offer a gift to those who survive us. My own parents died when I was in my early twenties. I missed them deeply and for years longed for more remembrances of them.

But I would be very cautious about bequeathing an avatar twin. I would need assurance that it would not produce unwanted complications.

My Hesitations

It'd be very difficult to build a legacy self free of my recency bias. The result would likely be an avatar that most resembles the person I've been for the last decade or so, a retired professor, husband and father to four grown kids, increasingly interested in Buddhism and obsessed with AI. That "me" is very different from the "me" who lived off and on for years in his van on the streets of San Francisco, or who taught eighth-grade English, or who worked for over a decade in macadamia orchards on the slopes of Mauna Kea.

Even if I could escape a recency bias, which past "me’s" should I include? The young, burnt-out sociologist, or the broke hippie? The farm laborer, middle-school teacher, peace studies professor, or Hawaii Kai retiree? Would my avatar give advice based on my academic life or on the survival tricks I learned living in my van? The database would likely default to my most recent, most documented self, but that might not be my most authentic one.

Maybe those externalities are not as important for my legacy twin as capturing the inner Houston, some basic character that's persisted across the years. But I don't know what that character is. I would like to think kindness is a prominent part of who I am. That's the quality I most aspire to have now. But "kind" is not how most people across the years would've described me. I don’t think I would even know how to curate a twin that accurately represents what other people see.

I would want to leave my best self to those who survived me. Why give them an asshole legacy when I could edit out the worst of who I've been?

The most human things about me are probably the parts I'd be afraid to include. I wouldn't tell that terrible secret thing I did, not as bad as murder but worse than stealing money from a friend. When I had to choose between speaking about the man who marched in Selma and the one who did not visit his dying high school friend, I’m pretty sure I know which I'd choose.

I once believed that authenticity required speaking honestly no matter the consequences. Now I value restraint. Silence seems like wisdom in many circumstances. I would want to build silence into my digital legacy. There is so much I would choose not to say.

But even if I could solve these practical problems, I worry about the impact on others. As I wrote in my post The Slow Death of Death Itself, digital legacies can drop survivors into a relationship with a digital legacy they usually never asked for. My wife married me for better or worse, not forever. An expectation of death parting us one day has been an implicit understanding in our marriage. I wouldn't want my digital legacy to become the family member who never stops talking. One who never gracefully fades into memory. It would be terrible to leave anyone with the burden of deciding when to delete me.

Beyond these practical and personal concerns, my choice sits within a larger debate. I know many in Silicon Valley imagine digital twins are just the beginning. Elon Musk and others see digital twins as steppingstones to full digital immortality. We evolved to make machines that usurp us, they say.

I'd rather die the old-fashioned way as a nonbiological life, even one possessing a machine-based consciousness, holds no attraction for me.

My Decision

So, I'm not going to create a legacy twin. But a choice like this isn't just mine; it's a question everyone will grapple with in this new era of potential digital immortality. What aspects of your unique self are you going to choose to preserve? How will we, as a species, define a “good” ending when endings are no longer guaranteed?

I'm confident in my decision, but I know it places me in what will probably be an increasingly shrinking minority. As people grow accustomed to curating personal brands and living with many Me's and many You's, they'll find it natural to curate versions that outlive them.

Beliefs in spirits, souls, ghosts, and other traces of life that survive death are common in most cultures and eras. Digital legacy twins seem another version of these ancient beliefs, beliefs that make death less frightening. People in AI-dominated cultures will probably pass on to AI-heavens, living as code for as long as servers run.

But this digital immortality holds little appeal for me. I've spent my career studying how humans make meaning. Now, at the end, I choose the meaning that comes from accepting an unequivocal end.

TO LEARN MORE:

A.I. Avatars and the Brave New Frontier of Life After Death - The New York Times

This is rich on so many levels. I'm so glad you made the decision you did. Even just physically it's challenging having someone look just like you, talk just like you and have the same background as you have. I can't imagine the impact of an avatar twin but I think the negative must outweigh the positive. Brilliant and thank you!

Hi Houston, Very interesting article — thanks for enlightening me to this “opportunity.” After thinking it over, I’ve decided I wouldn’t want to create another version of myself. I don’t see the point. Whether I do or don’t, it all ends up as a memory. We’re not here long, and the human race itself is just a speck in time. My focus is simply to do my best, raise my child with good values, and support her as she does the same for her own. At the end of my life, I just want to accept it and look forward to whatever’s next. If there’s nothing else, I won’t know any different. If there is, I’m curious to see what it will be. Thanks for the thought.